Bildband / Illustrated book

Part 01

Heaven’s Cross in the Luther Garden, Wittenberg, as seen by Ralph Richter

“What was my thinking? The sculpture should exude dynamism and “timeless modernity” in every detail. Only at second glance should the cross be perceived as a Christian symbol; the first impression should be of its overall appearance as a space-creating sculptural object integrated into the entire complex yet also centred on itself. It should satisfy all the criteria of high sculptural quality and unconditionally set itself apart from devotional art, a subject of frequent criticism.”

“We have just heard from the artist that he hopes people will raise their eyes and ask themselves what these stepped crosses mean. And with this up-lifted gaze he seeks to encourage people to continue inquiring into the meaning of their lives. And for each individual, each person, it is important – important for any person of faith and for any thinking citizen in society too – that he or she asks themselves why am I here in this world and what I can give the world? May this monument inspire such and other thoughts among the people who walk here. For the ‘Lutherstadt’ Wittenberg, it has added a further attraction that fosters a contemporary dialogue with the historical sites of the Reformation.”

“When we started planting the Luther Garden many years ago, we began with a stone cross. Today we are unveiling a flying cross. A light cross. A cross that grows as our trees grow here. A cross under which one can also find shelter and gather. A cross whose lightness and meaning unites everyone.”

“I enter the garden and find myself on a narrow path between young trees of different species. Looking more closely, I notice small plaques at the foot of each tree, telling me about a ‘partner tree’ planted in another location.”

“The Luther Garden project has attracted people from all parts of the world. But it was not only bishops, pastors and their parishioners who were involved in planting the trees.”

“Both sensually perceived and rationally analysed and considered, the peculiarity and diversity of the locations are reflected. Contemporary modernity is shaped and experienced like many ancient traditions that were once new and have proven their worth to this day.”

“Thomas Schönauer, whose art I collect with enthusiasm, is one of the greatest artistic innovators of our time and is even more uncompromising in his approach. He envisages high-tech materials in completely new constellations and environments, turns things upside down, causes bodies weighing tons to float and adhesives to flow.”

“The cross will last for a hundred years and more. This work of art shows that crafting metal is a creative job with a future.”

Part 02

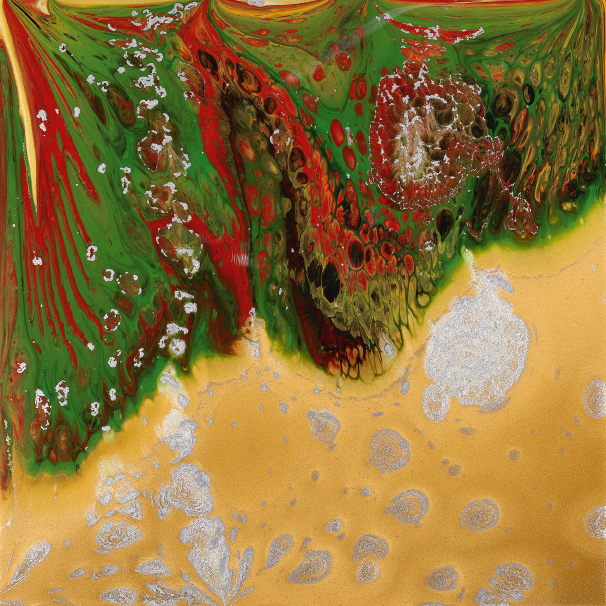

Thomas Schönauer CT-Universe / Luther Cycle

“After I’d become intensely preoccupied with the thematic realm of the Reformation, Luther, Wittenberg, the Luther Garden and the Heaven’s Cross, I increasingly felt the urge to devote my pictorial and painting energies within the technique I have developed to the Reformation. Ostensibly not the easiest endeavour for an abstract artist, but I found a bridge to it through the well-established colour code used by the master painters of that period, Cranach, Holbein, Dürer and others. And ultimately, what did the Reformation signify? In the broadest sense a struggle against the attitudes and pomp of the Roman Catholic Church, the venality of church offices, the sale of indulgences – that I condensed into the ‘gold formula'. This is how the ‘Luther' series came about.”

Page 47–65: CT 7–16 / 2018, Luther series, epoxy resin and pigments on stainless steel, 40 x 40 cm

“To equate art with innovation would probably be going too far, but for Schönauer art without innovation is inconceivable.”

“Heaven’s Cross in the Luther Garden impresses, awakens reverence, radiates dignity and invites us to meditate, to reflect on faith, on the meaning of human existence, alone or in communion with others.”

“A park planted with 500 trees from all over the world, whose paths were laid out in the shape of a Luther rose and led outwards from the Heaven’s Cross into the world – like the idea of the Reformation 500 years ago.”

“For Luther, pictures were value-free and religiously neutral. It is the viewer who makes them what they are. Thus the effect of a picture is left to our discretion and subjective disposition, free from any influence of authority. It is we who have the last word; the viewer not someone who unquestioningly marvels..”

“Does it make sense to point to a clump of trees and ask, ‘Do you understand what this group of trees says?’ In normal circumstances, no; but couldn’t one express a sense by an arrangement of trees? Couldn’t it be a code?”

“The Luther Garden with Heaven’s Cross exert their impact simply by their presence without recourse to words. To do justice to their unique appeal, the first volume of the publication primarily examines the site’s visual aspect. This hasn’t been done haphazardly, but photographed and “seen by” Ralph Richter who, having studied the Luther Garden in detail and in situ, knows succinctly how best to capture the impact and presence of the place in his photographs.

Wittenberg and the site of the Luther Garden are founded on a long historical tradition. Following on from this tradition, the implementation of the elaborate project ‘Luther Garden and Heaven’s Cross’ was only possible thanks to the help of numerous participants. The ensemble stands in a line of historical tradition that endures to the present and continues to preoccupy us today. To shed light on this background and reopen it to the viewer, the second volume offers a compilation of views about the project and brings various historical, art-historical and urban planning contexts into focus.”

Textband / Text book

Inhalt

Idea and background of the Luther Garden as a living monument

“The fact that the Reformation left deep traces in Germany is easy to grasp for any informed contemporary.”

Initiated by the Cardinal

How do you go about celebrating the 500th anniversary of the Reformation? Who is the host and to whom is such an event addressed? What should be the thematic focus behind it? When do you begin preparing for the festivities and how long should they last? All these questions suddenly came to the fore when the Roman Curial Cardinal Walter Kasper in 2003, during the plenary assembly of the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) in Winnipeg, Canada, brought up the 500th anniversary of the Reformation in 2017. Amazed and unbelieving faces were to be seen in the plenum of the plenary assembly when of all people the representative of the Vatican voiced a public reminder of this major anniversary of Martin Luther's Reformation. Up to that time none of the delegates had yet addressed any of the above issues. But that was soon to change.

A Reformation decade presenting the history of the Reformation’s impact

The fact that the Reformation left deep traces in Germany is easy to grasp for any informed contemporary. The impact of the Reformation on culture, science and education, on law and politics, together with the emergence of freedom and equality before God, became driving forces on the path to democracy. Their effect reaches deep into the society of the present. The impression on the German language made by Martin Luther's translation of the Bible is just as significant as the commitment of municipal and state institutions to provide school education of boys and girls (!) and welfare for the poor. Finally, important impulses for the separation of state and church also derived from Luther's Reformation. In order to fully appreciate and approach this range of topics directly or indirectly initiated by the Reformation, the Protestant Church in Germany finally launched a whole decade dedicated to the Reformation. In the course of ten years, central issues such as Reformation and politics, Reformation and music, Reformation and freedom, Reformation and education were addressed in cooperation with major participants from civic society and the state. These activities were supported by the German Bundestag, which on 6 July 2011 assessed the significance of the Reformation thus: “The theses submitted by Martin Luther on 31 October 1517 are regarded as the trigger for the Reformation. Over the past 500 years, it has had a formative effect on society and politics not only in our country but also throughout Europe and the world. According to tradition, over 400 million Protestants see their denominational and important spiritual roots in the theses that Martin Luther is said to have nailed to the door of Wittenberg Schlosskirche (All Saints’ Church). The 2017 anniversary of the Reformation will be an ecclesiastical and cultural-historical event of world standing (...)” (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Heaven’s Cross by Thomas Schönauer in front of the neo-Gothic Schlosskirche (All Saints’ Church) in Wittenberg

The Reformation as a citizen of the world

Looking at the earlier anniversaries of 1617, 1717, 1817 and 1917, it quickly becomes clear that they were celebrated in clear demarcation from the Catholic Church and from hostile neighbouring countries such as France. Official statements and documents contain strong anti-Catholic and anti-French polemics. By contrast, preparations for the 2017 anniversary showed that cooperation and concrete collaboration between the churches and their congregations have long since become the norm. On an international level, the Vatican and the LWF have been engaged in theological dialogue for over fifty years, leading to a far-reaching form of reconciled coexistence. History was already made in 1999 with the signing of the “Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification”. For the first time Catholics and Lutherans worldwide agreed on a consensus concerning fundamental questions of Christian doctrine. In preparation for 2017, the LWF and the Vatican produced the document “From Conflict to Community” in which, for the first time, the history of the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation was jointly reappraised and both parties reciprocally asked each other to be forgiven for past mistakes and aberrations.

The document went on to express the common faith and called for a joint Lutheran and Catholic commemoration of the Reformation. This was put into practice in a service on Reformation Day 2016 in Lund Cathedral, which for the first time was led jointly by a Roman Catholic Pope (Francis I) and a President (Bishop Dr. Munib Younan) and a General Secretary (Pastor Dr. h.c. Martin Junge) of the LWF. This also gave rise to far-reaching forms of reconciliation and mutual recognition with other church communities of the world such as Anglicans, Reformed, Orthodox, Methodists and Mennonites. One reason for this development is also the fact that the core statements of the Reformation have found worldwide dissemination and recognition: for Christians, the Holy Scripture is the key document of orientation; Christ is the unequivocal reason for orientation and salvation in the believer’s relationship to God; faith is the central medium of the perception of God. These principles can be found in the self-concept of many churches worldwide. Nevertheless, in preparation for 2017, the question arose as to how these encouraging ecumenical advances might not only be presented scientifically and liturgically, but also made enduringly and symbolically visible.

Fig. 2: The Luther monument, designed by Johann Gottfried Schadow, on Wittenberg’s market square, 1817

A symbol of reconciliation between the churches

In the 19th century, monuments to Luther in bronze were produced in numerous places to keep alive the memory of the Reformation. They can still be admired today in many central squares of German cities (Fig. 2). As a rule, Luther is depicted larger than life as an energetic, teaching, protesting figure citing the Holy Scriptures. In preparation for the first important Reformation anniversary in the 21st century, landscape architect Andreas Kipar and Norbert Denecke, a member of the High Consistory, asked themselves what manner of contemporary monument could symbolise the festivities in 2017. In any case, it would have to be located in Wittenberg as the place where the Lutheran Reformation began. At the same time, however, the monument should also lend expression to the international dimension of this global movement. The confessional character of the churches involved should be just as perceptible as their ecumenical solidarity. What had been separated in the past had now grown together. Grow! This keyword gained central importance in subsequent deliberations. It has grown a little and is supposed to keep growing. Didn't Luther also talk about the signal of hope in the apple tree? “Even if I knew that tomorrow the world would go to pieces, I would still plant my apple tree.” Even if the authenticity of this dictum has not been verified, it nevertheless speaks of Martin Luther’s unshakeable belief in hope and faith. So why not plant apple trees? Why not let representatives of churches from all over the world plant trees as a sign of common faith and unshakable hope for a better world? Why not let a park emerge as a symbol of hope for the growth of the individual Christian churches and their communion with one another for the good of the people and for the glory of God? Why not have 500 trees planted by 500 churches, dioceses and church institutions for 500 years of Reformation, thus documenting their reconciled association with the Reformation that emerged from Wittenberg? The “Luther rose”, Martin Luther's personal coat of arms with a cross at the centre, could give the symbolic garden a focusing core. So in 2006 the idea of creating a “Luther Garden” at the place of origin of the Lutheran Reformation emerged (Fig. 3). But with this concept there was still plenty to do. For the difficult questions of how and where had not yet been answered.

The city's ramparts as a site for the Luther Garden

The first person to turn to when it came to finding a site for the park in the “Luther city” Wittenberg was the city mayor. Eckhard Naumann was persuaded to back this idea in 2006. How would the Lord Mayor react to this proposal, while elaborated in draft designs, but ultimately still vague? At a personal meeting in the mayor's office Kipar and Denecke modestly asked whether the city could provide an area alongside the Elbe to create the Luther Garden. The Lord Mayor rejected the idea, pointing out that the site would quickly be destroyed by the next Elbe flood. But Kipar and Denecke’s disappointment turned to enthusiasm when the Lord Mayor went to the vast city map behind his desk and offered to provide the so-called Andreasbreite on the city's ramparts for this project. Even though it was clear that the various municipal bodies and authorities still needed to be persuaded to support this plan, there was no doubt that this would be an ideal location for the Reformation project.

In contact with 500 churches and dioceses on 6 continents

But how can a park express the connection of churches from all over the world with the original source of the Lutheran Reformation? How could one give visible form to the process by which churches that as a result of the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation had once reciprocally condemned and split away from each other are today bound together in reconciled fellowship? The challenge was therefore to directly address these churches from different continents and to invite them to set a visible sign of reconciled solidarity in Wittenberg. To this end, the project idea was supplemented by a procedure in which in addition to the tree in Wittenberg each church would also plant a “partner tree” in a central place by their own church. In doing so, the idea was to make a clear reference to the Reformation project “Luther Garden in Wittenberg”, thus lending visible form to the interconnection between the various churches.

Even though the Reformation began in Wittenberg, it is now firmly rooted throughout the world. But the crucial question remained: how was it possible to communicate with 500 churches and ecclesiastical institutions the whole world over and convince them to actively participate in a Reformation project in Lutherstadt Wittenberg? This required a strong institutional and, above all, internationally networked partner. The LWF needed to be persuaded to make the Luther Garden its own project and to open channels of communication to its 145 member churches in 98 countries. Especially since its member churches have excellent contacts to further churches of other denominations. In 2007, a crucial meeting was held at the LWF headquarters in Geneva, where the former Lord Mayor of Wittenberg, Naumann, the landscape architect Kipar and, as a member of the High Commissary, Denecke met with the LWF General Secretary, Father Dr. Ishmael Noko. All participants quickly agreed that the Luther Garden in Wittenberg should adopted by the LWF as a central Reformation project. In the November 2007 issue of Lutheran World Information, a photo of handshakes between the participants was featured under the heading: “Wittenberg plans a Luther Garden” (Fig. 4). The project had been accepted by the LWF, opening the way to promoting tree planting in the Luther Garden and the partner churches around the world. In order to make the project known not only in Europe, but also in the many countries of Africa, Asia, Latin America and North America, communication had to be effected in different languages. This time-consuming and personnel-intensive work was carried out by the LWF Centre Wittenberg, which opened in 2008. Over the following years its director, Pastor Hans Kasch, and his assistant, Mrs. Annette Glaubig, were in daily contact with churches all over the world to ensure that, for all the problems related to language, culture, finance and communication, the Luther Garden project became reality.

Fig. 3: Motif of the Luther rose from the entrance to the Luther House, Wittenberg

Fig. 4: Photo of the participants shaking hands under the heading “Wittenberg plans a Luther Garden”, from the November 2007 issue of Lutheran World Information: DNK/LWB Managing Director and member of the High Commissary, Norbert Denecke, landscape architect, Dr. Andreas Kipar, Lord Mayor Eckhard Naumann from Lutherstadt Wittenberg, LWB General Secretary Pastor, Dr. Ishmael Noko, Pastor Chandran P. Martin, Deputy LWB General Secretary, and LWB Communications Director, Karin Achtelstetter (from left to right).

With the blessing of popes and church leaders.

A project of this scale must be developed and maintained on very different levels. The first thing required was acceptance among the population and local authorities. The project was promoted at numerous meetings and public debates, especially as a considerable sum of public money needed to be made available for the park’s construction. The incorporation of the Luther Garden into already existing buildings, such as a neighbouring playground, also had to be dealt with. Thanks to fruitful discussions and a strong financial commitment by the Church as a project partner, this hurdle was also overcome. Accordingly, flexibility and necessary enthusiasm on the part of the landscape architect and the project's lead partner were in constant demand. They had to stick to the basic idea and the basic concept even if difficulties arose, or develop them further until a solution was found that was acceptable to everyone involved.

After all, such a global ecclesiastical project also requires the support of the heads of the churches. This was a prerequisite for all the individual churches, dioceses and ecclesiastical institutions subscribing to this project.

In the following years, meetings with important church leaders were used to promote the Luther Garden and the concept behind it. By 2009 Patriarch Bartholomew I had already given his promise to support the project for the Orthodox churches. And the Catholic Church immediately signalled its participation in the project through the person of Cardinal Kasper. The Luther Garden received additional support in the course of a private audience with Pope Benedict XVI in 2011 and during a private audience with Pope Francis in 2014. At the plenary assembly of the World Council of Churches in Busan (Republic of Korea) in 2013, the project was also presented to other leaders of the Christian World Communions. In 2014, the project received support from Archbishop Justin Welby, who as Archbishop of Canterbury is leader of the Anglican Church worldwide.

However, the idea was not merely to keep the church partners informed about the project, but also to encourage them to plant a partner tree in their own contexts with reference to the Luther Garden in Wittenberg. This occurred, for example, during the visit of Pope Benedict XVI in 2011, when the Vatican's partner tree, an olive tree, was planted in the courtyard of the Papal Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls in Rome by Kurt Cardinal Koch in the presence of German Lutherans. It was hardly an everyday activity for a full-fledged Curial Cardinal to personally plant a tree in the shadow of the imposing basilica. But this symbolic act clearly expressed that the Roman Catholic Church also acknowledges its reconciled connection to the Lutheran Reformation.

Visits by crowned heads culminating in a Heaven’s Cross

The Luther Garden project has attracted people from all parts of the world. But it was not only bishops, pastors and their parishioners who were involved in planting the trees. Members of government, ambassadors and representatives of towns and municipalities also visited the park. During their visits to Wittenberg, the Queen of Denmark, Margrethe II, as well as the royal couple from Sweden, Carl XVI Gustav and Silvia of Sweden, also took to the spade.

In 2016, a long-awaited plan finally came to fruition: the design of the Centre in the Luther Garden. The artist Thomas Schönauer presented sketches for his design of the cross to be located in the middle of the central Luther rose.

The plans were so convincing that not only renowned sponsors, but also the “Lebendige Stadt” Foundation immediately offered their support for the “Heaven’s Cross in the Luther Garden”. Its inauguration took place in conjunction with a meeting of the LWF Council with delegates and ecumenical guests from around the world. German Federal President Joachim Gauck, who attended the inauguration ceremony, had the following to say during a subsequent discussion: “We have just heard from the artist that he hopes people will raise their eyes and ask themselves what these stepped crosses mean. And with this up-lifted gaze he seeks to encourage people to continue inquiring into the meaning of their lives. And for each individual, each person, it is important – important for any person of faith and for any thinking citizen in society too – that he or she asks themselves why am I here in this world and what I can give the world? May this monument inspire such and other thoughts among the people who walk here. For the ‘Lutherstadt’ Wittenberg, it has added a further attraction that fosters a contemporary dialogue with the historical sites of the Reformation.”

“After all, such a global ecclesiastical project also requires the support of the heads of the churches.”

A symbol of hope: an olive tree on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem

The plan worked. The Luther Garden in Wittenberg comprises 500 trees. In addition to the central Luther Garden on Andreasbreite, there are two other sections on the city ramparts, one right next to the Luther House. The trees were planted by churches from some 100 countries. Furthermore, the planting of the partner trees in many churches around the world was done very imaginatively. Churches in Africa and Latin America have for their part created entire Luther Gardens. One European church planted 500 trees at once on the grounds of its churches, diaconal institutions and training centres. Many churches were inspired by the ecumenical dimension of the project and planted their trees in Wittenberg together with their ecumenical partners. The German National Committee of the LWF has planted a partner tree on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, thus sending a signal of hope and solidarity with the LWF's work in Jerusalem and Palestine.

The Philippine Lutheran Youth League was inspired by the Luther Garden in Wittenberg and planted 500 trees all over the country. This has been accompanied by a campaign to raise awareness of climate change. As part of this, youth camps and seminars on the causes of climate change and on ways of mitigating damage will be held. In other words, the Luther Garden project continues! This worldwide exchange will keep going and the trees will also serve as enduring witnesses of the understanding behind the commemoration of the 2017 anniversary. Who can know what manner of self-image and what kinds of thematic focus will drive the 550th anniversary of the Reformation in 2067? But it can be safely assumed that the Luther Garden and its partner trees throughout the world will bear witness to the character of the celebrations in 2017.

“Who can know what form of self-image and what kinds of thematic focus will drive the 550th anniversary of the Reformation in 2067? But it can be safely assumed that the Luther Garden and its partner trees throughout the world will bear witness to the character of the celebrations in 2017.”

Heaven’s Cross in Wittenberg – a contemporary challenge

“The aim of the plan was to create a park-like garden with 500 planted trees to mark the 500th anniversary of the Reformation in 2017.”

Eight years ago already I met landscape architect Andreas Kipar at the “behest” of our mutual friend Werner Küsters. That was not so easy, because to synchronise my schedule with that of the Milan-based, internationally active, Andreas Kipar, who at that time also had a foot in Germany with a branch of his office in Duisburg, required quite some effort.

Our first meeting very quickly prompted us to agree that, besides sharing similar views on an array of topics and the same opinion, greater convergence was required if we were going to embark on joint action. Today we would say that no good conclusion will follow from pursuing a straight and direct course, without looking left and right, towards a purpose and goal that is defined in advance. Bringing together landscape design, architecture and art is a complex process and requires exploring many individual questions before an answer appears on the horizon.

Why do I say this? It took a number of joint projects such as our participation in the International Garden Show (IGS) in Hamburg, winning the competition to redesign the former Moscow Central Airport (Khodynka Park) and other projects to manifest the core competence, quality and source of inspiration of our cooperation: the ability to feel and appreciate the underlying vibrations of the tasks we were facing, the places and people involved.

Exactly ten years ago, Andreas Kipar was commissioned by the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) to develop design ideas as a draft for the Luther Garden in Wittenberg in the centrally located Elbe meadows, a stone's throw away from the Schlosskirche (All Saints’ Church), where Martin Luther is said to have nailed his 95 theses to the main gate. The aim of the planning was to create a park-like garden with 500 planted trees to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Reformation in 2017.

Kipar's design was wonderfully adapted to the local conditions, in particular to the overall shape of the available green space and the already existing urban structures such as roads, pathways, trees, and planned infrastructural innovation measures such as the new railway station due to be created for the festivities (Fig. 1). He developed an extremely exciting dramaturgy based on an oval, incorporating it into the overall structure, with defined curved lines of trees converging on a central point. The hub consists of a square of about 40 metres in diameter, whose centre was marked by a cross formed by large natural pebbles inserted into the ground.

Fig. 1: The Luther Garden in Wittenberg before the erection of Heaven’s Cross in 2017.

“I had encountered such a high degree of authenticity, identity and value that, on the one hand, it would have been a catastrophe to deviate even marginally from this level, yet, on the other, this superb overall situation had precisely the effect of a springboard capable of launching us into a focalisation of quality.”

Over the years tree after tree was planted and they grew and grew. As the anniversary year approached, the decision-makers as well, of course, as Andreas Kipar, became increasingly convinced that within the overall design of the Luther Garden and its centre the stone cross did not represent a truly outstanding, conclusive solution. On the basis of and trusting in our previous shared experience of cooperation as described above, Andreas Kipar asked me whether I was interested, whether it appealed to me, whether I would even hazard to think about a design for this central place.

My inquiries regarding clear spatial, political, religious, financial ideas or guidelines resulted in a very general picture: what was envisaged was a space of focused reflection where individuals or groups might feel comfortable, perhaps find shelter, but also where an assembly, prayers or mass could be held. And it was assumed that this object, this installation, would be built for temporary use, for the one-year duration of the festivities commemorating the “Luther Year”. What a challenge!

Before I even started forging concrete thoughts, I made my way to Wittenberg, where I had never been before in my life. Of course, I took a lot of intellectual baggage with me on my first visit to Wittenberg in December 2013: the history of the Reformation – in my view – as a precursor that prepared the way for the Enlightenment, knowledge of Luther's life and work, his anti-Semitic views, the 95 theses nailed to the door of the Schlosskirche, Lucas Cranach’s portraits, the atheistic state doctrine of the GDR era, its consequences and much more besides.

It was freezing cold on the day I was due to meet Pastor Hans W. Kasch, director of the LWF Centre in Wittenberg, in the Luther Garden. What a place, what an individual! All the mental baggage I’d brought with me instantly and completely faded into the background. Despite the cold, which is usually an anathema for me and my imagination, all I felt was the immense energy and aura of the place, the space, and the warm, engaging manner of Herr Kasch and his extraordinarily informative commentary. Two hours spent in the energetically warming icy cold of the Luther Garden, then an extended tour through Wittenberg, which was undergoing careful conservationist restoration as a historical site, followed by two glasses of mulled wine created the foundations for my first relevant thoughts.

The long return journey from Wittenberg via Berlin to my studio was highly absorbing. I could barely keep the cocktail of thoughts and feelings in check. As an artist, it was now important for me to set the priorities that felt relevant from my point of view. For me this meant above all to allow the dramaturgy, the tension, the aura and the energy of what had already been achieved in this place to flow into each aspect of my creative thinking. I had encountered such a high degree of authenticity, identity and value that, on the one hand, it would have been a catastrophe to deviate even marginally from this level, yet, on the other, this superb overall situation had precisely the effect of a springboard capable of launching us into a focalisation of quality.

An intensification of quality was my guiding idea and feeling, which per se contradicted the call for a temporary installation. It is and was about taking up the river and streams that transport and convey the curved line of trees from the periphery to the central square and letting these flow back. The dynamism of the site had to flow into and define the object, whatever it ended up being. Very quickly I was taken by the idea that the only adequate response to the horizontal dynamism of the rows of trees – fully aware that by virtue of their natural growth they also harboured a vertical dynamism – would come from developing a multi-layered structure both in lateral and upward directions.

What had been created that I had encountered thus far consisted not only of the curved rows of trees and the square with the stone cross lying in the ground. The cross itself was framed yet again in a robust, but organically shaped ornament, the so-called “Luther rose”. This Luther rose is five-leaved, interpreted here with lawn elements arranged in a corresponding shape with a lime tree planted in the space between each one of them. This altogether organic basic form never once caused me to call into question the cross as a hermetically rectangular element and hence the antithesis to the curved forms, neither in formal terms nor as a symbol, since the people responsible for the previous design of the site had had good reasons for locating it there and also it wasn’t contrary to my own opinion of what would be feasible in this overall context.

To put it in a nutshell, I “had to” formally and symbolically break with the single layer, with the single dimension of the cross lying in the ground. My decision to create a three-tiered cross was fundamentally informed by reflection on my own cultural identity with Jewish, Huguenot roots and a Catholic upbringing, by an awareness of the Christian Trinity of God the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, but also of the trinity of the gods Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva in the world religion Hinduism and, fundamentally, of the ecumenical spirit of the LWF underlying the creation of this Luther Garden. But in all this it was also very important to me, corresponding to the idea of the Reformation, for the lowest level of the cross to be flush with the ground.

A three-tiered cross was a first satisfying step on the way towards the final idea. Then I soon began thinking that the dynamism of trees’ growth could be echoed in and symbolically transposed by giving different dimensions to the three crosses. And if I then let them grow from bottom to top, i.e. increase in size, not only would I create a formal arc of suspense to the thinner treetops, but would also lend my skyward surging form greater dignity and meaning, as well as, in purely functional terms, also giving them a kind of shelter (roof).

Then the question of construction and materials arose, primarily as a result of the claim to the contemporaneity of made by a two-thousand-year-old symbol. The idea of horizontally layering a cross in different dimensions was already a first step away from tradition towards modernity. My aim was now to achieve the sense of lightness that, for all their great weight, is inherent in all my sculptures and thereby also release from the weight of the Christian symbol. A first model was made with a wooden cross flush with the floor – man becomes dust. The crosses ascending to the sky stood on thin metal supports, while the crosses themselves consisted of a semi-transparent modern material, in this case acrylic glass, as this to me seemed altogether plausible for a temporary installation.

Now I had to “float” the idea, the model and my explanatory text, so I first presented it to Andreas Kipar. He was so impressed that my design was quickly passed on to the LWF's decision-makers, above all Norbert Denecke. As they gave the green light, the next step was to put together an overall package suitable for presentation to Wittenberg's city leaders and to sponsors such as the “Lebendige Stadt” Foundation. To do so I was able to draw on the help and experience of my friend, the architect Bernhard Bramlage, who had carried out numerous projects in both church and heritage conservation contexts. The outcome of the presentation was that the city leaders and all the other decision-makers involved concurred that this “Heaven’s Cross”, the name my design quickly adopted, should serve as the centre of the Luther Garden, and furthermore also in the long term, beyond the year of the anniversary celebrations.

Naturally, this decision gave me great satisfaction, but it also presented me – or rather us – with unforeseen new challenges. The materials, the statics and, of course, the budget had to be completely rethought. I quickly decided in favour of Corten steel, stainless steel and/or aluminium. Corten steel is a so-called weather-resistant construction steel, which through a special alloy forms an oxide, i.e. a layer of rust; this in turn prevents further rusting. For the cross flush with the floor we intended to use this material, which suggests transience. The crosses that were to rise up into the sky and grow in size were meant to absorb the light and disperse it over the surfaces, an effect we intended to achieve by treating the surface of the outer skin of stainless steel or aluminium sheets to a special grinding process (Figs. 2 + 3). They symbolise timelessness, eternity.

Fig. 2: Assembly of Heaven’s Cross in May 2016

Fig. 3: Assembly of Heaven’s Cross in May 2016

The material character was now largely defined and a generous donation from the entrepreneur Erika Zender had also given the project’s funding a great boost, but we still had no feasible statics and thus also lacked the ensuing construction plan. This process took longer than expected for the true challenge lay in the sheer size of the object – the top cross measures 14.5 meters long x 11.0 meters wide and 4.5 meters high – which I “insisted” should rest on supports as slender as possible. We finally managed to find a congenial partner in the metal construction company Henschel from Barby, a small town not far from Magdeburg.

Eckhard Henschel instantly understood my thinking: the sculpture should exude dynamism and “timeless modernity” in every detail. Only at second glance should the cross be perceived as a Christian symbol; the first impression should be of its overall appearance as a space-creating sculptural object integrated into the entire complex yet also centred on itself. It should satisfy all the criteria of high sculptural quality and unconditionally set itself apart from devotional art, a subject of frequent criticism – otherwise I would have failed both from my own perspective and by my own standards as an artist.

The volumes of the bodies of the respective crosses took shape as the core of what was statically feasible and of the above-described aspirations. The cross bodies we developed resemble a modern jet wing and in constructional terms are also very similar to the frame structures of an aircraft wing. This statically extremely dynamic form capable of bearing considerable loads, which over a width of three metres tapers from a voluminous centre almost to zero towards the outer edges, thereby also counterbalancing wind loads, made it possible to dispense with a support at the centre of the cross as had originally been thought necessary. For me this represented a great breakthrough, to breathe lightness into the overall sculpture as I’d dreamt of doing. For reasons of cost and handling we opted for an outer skin made of stainless steel sheet, which, as previously mentioned, uses a special finish to disperse existing natural light into the surface, hardly reflecting it and thus contributing to the sense of lightness.

Producing good plans, drawings and construction plans is one thing. But to construct and ultimately assemble such a complex, multi-component object consisting of altogether twelve tons of steel is a further, major challenge. Here too, Herr Henschel, his splendid team of employees and I discussed and smoothly fine-tuned numerous details. During the crucial stages of pre-assembly, the way to Magdeburg was never too far for me to go – nor, of course, were the two final assembly days in Wittenberg itself. With an inauguration event that was perfectly organised by the LWF and attended by the German Federal President and many distinguished figures from churches, civic life and politics, the entire process that had taken almost three years came to a very worthy and thought-provoking conclusion.

To conclude, it remains to be said that “Heaven’s Cross” was certainly one of my greatest artistic challenges with regard to the contexts of landscape design, urban planning and in historical, spiritual and ideological terms, as well as in relation to its formal and constructive complexity (Fig. 4). And without hesitation I can also say that I consider “Heaven’s Cross” to be the most important work in my artistic career so far. My thanks go to everyone involved!

Fig. 4: Heaven’s Cross in the Luther Garden from a bird's eye view

“My thanks go to everyone involved!”

“The aim of the plan was to create a park-like garden with 500 planted trees to mark the 500th anniversary of the Reformation in 2017.”

Eight years ago already I met landscape architect Andreas Kipar at the “behest” of our mutual friend Werner Küsters. That was not so easy, because to synchronise my schedule with that of the Milan-based, internationally active, Andreas Kipar, who at that time also had a foot in Germany with a branch of his office in Duisburg, required quite some effort.

Our first meeting very quickly prompted us to agree that, besides sharing similar views on an array of topics and the same opinion, greater convergence was required if we were going to embark on joint action. Today we would say that no good conclusion will follow from pursuing a straight and direct course, without looking left and right, towards a purpose and goal that is defined in advance. Bringing together landscape design, architecture and art is a complex process and requires exploring many individual questions before an answer appears on the horizon.

Why do I say this? It took a number of joint projects such as our participation in the International Garden Show (IGS) in Hamburg, winning the competition to redesign the former Moscow Central Airport (Khodynka Park) and other projects to manifest the core competence, quality and source of inspiration of our cooperation: the ability to feel and appreciate the underlying vibrations of the tasks we were facing, the places and people involved.

Exactly ten years ago, Andreas Kipar was commissioned by the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) to develop design ideas as a draft for the Luther Garden in Wittenberg in the centrally located Elbe meadows, a stone's throw away from the Schlosskirche (All Saints’ Church), where Martin Luther is said to have nailed his 95 theses to the main gate. The aim of the planning was to create a park-like garden with 500 planted trees to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Reformation in 2017.

Kipar's design was wonderfully adapted to the local conditions, in particular to the overall shape of the available green space and the already existing urban structures such as roads, pathways, trees, and planned infrastructural innovation measures such as the new railway station due to be created for the festivities (Fig. 1). He developed an extremely exciting dramaturgy based on an oval, incorporating it into the overall structure, with defined curved lines of trees converging on a central point. The hub consists of a square of about 40 metres in diameter, whose centre was marked by a cross formed by large natural pebbles inserted into the ground.

Fig. 1: The Luther Garden in Wittenberg before the erection of Heaven’s Cross in 2017.

The meaning of trees. 500 years Reformation: how Wittenberg with its interactive Luther Garden embraces the world

In the beginning was the tree

The archetype of the tree stands at the hub of the cosmos and connects heaven and earth. This archetype spawned the sacred groves of antiquity and gave rise to the Garden of Eden as an image of paradise. Light and shadow, life and change, fruit and temptation play a special role not only in Christianity. Gardens, “girded land”, are a symbol of people’s quest for an ordered world, an expression of a longing for peace. Maria Jepsen, a Protestant Lutheran theologian, once wrote that the garden was “a gift of God to us human beings”. A “vaccine” which makes us aware of life, its pleasures and dangers, “and which teaches us to be more patient”.

Gardens inspire. They combine cultural needs with natural conditions. They are places of social attachment and societal exchange. In a sense, every garden is unique. It intrinsically harbours an overall historical and spiritual dimension, yet at the same time has to compete very concretely with reality in situ and engage in a dialogue with both the urban and the social environment.

In the shadow of a cedar

The Luther Garden in Wittenberg belongs to the tradition of gardens as places of encounter and reflection. It reflects the notion of togetherness. For this garden’s particular feature is that with its trees it is growing not only in the Lutherstadt on the Elbe but also in numerous other places all over the world. The idea is that any church and religious community throughout the world can sponsor a tree in the Luther Garden and that each tree they plant in Wittenberg is matched by a partner tree planted in a garden of their home parish or community (Fig. 1).

It was perhaps no coincidence that this idea was born in the shadow of a 150-year-old cedar in the small churchyard of the Lutheran Reformed Congregation in Milan. It occurred in the very centre of the Lombard metropolis in summer 2006, shortly before the so-called Reformation Decade 2007–2017: “Even if I knew that tomorrow the world would go to pieces, I would still plant my apple tree”. The sentence attributed to Martin Luther is an appeal to unconditional trust in everything that can grow beyond us. Similar to Luther’s reform movement, which started from the small town of Wittenberg and grew to span the whole world, giving the city its historical significance.

Fig. 1: Planting plan of the Luther Garden at Andreasbreite, tree no. 1 – 292

As a landscape architect you learn to think in images, to draw plans, to design and plant gardens and parks. But how do you transport an idea from Milan to Wittenberg? Who could open doors for me there, who was likely to show any interest at all in an interactive, growing and world-spanning monument to the Reformation anniversary? These were questions I could discuss with Norbert Denecke. For many years he had been pastor of the Milan congregation and is now active as a member of the High Consistory and as managing director of the German National Committee of the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) in Hanover. And it was Norbert Denecke who helped me open the first doors.

The language of the garden

Within just a few months the idea grew into a project. Talks with Ishmael Noko, then General Secretary of the LWF, Eckhard Naumann, former Lord Mayor of Lutherstadt Wittenberg, and Siegfried Kasparick († 2016), then the local provost, signalled general agreement.

The first project sketch was accomplished in autumn 2006. The basic oval shape reflects the site in the ramparts and the symbolism of the garden. At the centre of the design is the circular shape of the Luther rose with a diameter of 40 metres. It represents the 40 days Moses spent on Mount Sinai as well as the period Jesus fasted in the desert. It develops into an ellipse with a width of 70 meters – a number generated by the product of the prime numbers 7 x 5 x 2. The distance between the focal points of the ellipse is 95 metres and stands for Luther’s 95 Theses. The inner structure is made up of a celestial arch – it too spans from the zenith to the edge of the ellipse, 95 metres in each direction – and of the five avenues of the worlds, which point from the Luther rose towards the Elbe and symbolise the connection to the five continents.

This is the language of the garden, the meaning of the trees: they were to be 500 in number, commemorating the Reformation of 1517 in the Luther Garden and the city. So churches from all over the world were invited to sponsor a tree and, parallel to this, to plant a tree in the grounds of their own churches at home. The idea had become a project and was taking shape.

But it was still two years before the foundation stone of the Luther Garden was laid. Plans were yet to be approved and binding sponsorship commitments between the LWF and the City of Wittenberg signed. And on a local level much was done to promote sympathy and support within the city community.

A place of encounter and change

But finally, on 20 September 2008, the foundation stone, or rather the cornerstone, was laid in the central cross of the Luther rose. The American bishop and president of the LWF, Mark S. Hanson, had travelled here for this purpose. Together with him, the leading bishop and chairman of the German National Committee of the LWF, Johannes Friedrich, and the former mayor of Wittenberg, Eckhard Naumann, laid the cornerstone of the cross. The artistic design of the centre of the Luther rose was at first deliberately left open – but the shape of the cross was clearly established.

The first trees were planted on 1 November 2009 by representatives of the Christian world churches. The five lime trees within the Luther rose – the lime tree symbolises community, justice and assembly – are each dedicated, respectively, to the Roman Catholic, the Orthodox and the Anglican Churches as well as to the Reformed and Methodist World Federations. By now, at the latest, it became clear to everyone that no further monument of the conventional kind was to be erected here; instead, however, there would be something of an interactive, international and ecumenical nature – a place of encounter and of change (Fig. 2). And indeed, churches from all over the world accepted the offer to plant a tree, thereby underlining their direct connection to the Reformation and to the Lutherstadt Wittenberg. Beginning as a ripple in Wittenberg, waves have now spread out as far as Rome, Jerusalem and Australia.

Fig. 2: The Luther Garden in Wittenberg with the planted Luther trees

“The artistic design of the centre of the Luther rose was at first deliberately left open – but the shape of the cross was clearly established.”

“The establishment of a centre of the Lutheran World Federation in Wittenberg was important both for local cooperation and worldwide contacts. With loving care and pragmatic work, Pastor Hans W. Kasch, as its director, and his staff have built up a service centre for visiting groups from all over the world, a place we would not want to do without again”.

The establishment of a centre of the Lutheran World Federation in Wittenberg was important both for local cooperation and worldwide contacts. With loving care and pragmatic work, Pastor Hans W. Kasch, as its director, and his staff have built up a service centre for visiting groups from all over the world, a place we would not want to do without again.

Heaven’s Cross as roof and prayer

Lime trees on the celestial arch, meadow orchards between the avenues and small-crowned tree species such as maple and ash, whitebeam and trumpet tree were gradually growing into unity in diversity, while a privet hedge marked the outer frame. The monument came alive and swelled. Just the design of the centre still remained open. A tender for design proposals was rejected. I was hoping that the site would have an inspiring effect and invited Thomas Schönauer to come and visit Wittenberg and its Luther Garden. As a visual artist he had long devoted himself with his enamelled steel sculptures to the tension between corporeality, free space and spiritual expression. Would he respond to the genius loci?

We weren’t disappointed. Thomas Schönauer’s sensitive yet persistent work, his ceaseless exploration through contacts and conversations finally gave rise to his three-part work Heaven’s Cross, which congenially combines the principle of growth and the lightness of the garden’s layout with the idea of a new, sweeping sky to provide shelter and shade at the same time. A roof for meditation, for coming together and for prayer. It was inaugurated on 15 June 2016 in the presence of the then German Federal President, Joachim Gauck.

In the meantime, all 500 sponsorships have been awarded. This partnership concept has initiated numerous communicative processes and interactions over the past ten years. The Luther Garden, maintained by the city of Wittenberg and frequented by residents and visitors alike, is an expression of common growth achieved in addressing the challenges of ecumenism.

There are Luther Gardens are everywhere. Wittenberg is everywhere. As an expression of finding hope in a future of peaceful coexistence on this planet. Growing together and growing closer are the two most important aspects to have accompanied and inspired me in this project.

Supporting the arts from an entrepreneurial perspective

Successfully managing and developing a company over decades means being able to remain true to yourself as you constantly change. Entrepreneurs do not use crystal balls to stay ahead of market demands and customer needs. Successful companies never tire of seeking new ways to imagine and view a given situation. This attitude is the fertile ground from which many German companies draw their considerable innovative strength. Germany’s family-run middle class businesses in particular thrive on this inexhaustible power of renewal. Such medium-sized companies are often not especially glamorous, yet without their engineering skills many a great innovation from Silicon Valley, for example, has often remained a mere pipe dream.

I come from such a family business. Our company had long belonged to Swiss corporations until my father, Dr Alois Franke, dared to undertake a management buy-out in 1993. Even while employed as a managing director, he was an entrepreneur through and through. He felt committed to the company location, its staff and the services they provided. While my brother and I are “only” the second generation to be working for Aluminium Rheinfelden, there are other employees who have remained loyal to our company for five generations already. A family business is not just an entrepreneurial family; a workforce that has grown like this is a family in itself.

Being bold, willing to take risks, yet also maintaining moderation, bringing on board everyone involved, even enthusing and galvanising them, injecting experience and insights into new contexts, remaining undaunted, persevering and tireless, possessing great stamina to endure frustration, fascinated by detail, humorous and holistic, yet with meticulous knowledge as to the core of success, nurturing and protecting – this is the soil in which established companies foster innovation.

Thomas Schönauer, whose art I collect with enthusiasm, is one of the greatest artistic innovators of our time and is even more uncompromising in his approach. He envisages high-tech materials in completely new constellations and environments, turns things upside down, causes bodies weighing tons to float and adhesives to flow. It is as if he had abolished the laws of nature, or at least overridden them, and thereby opens the viewer’s eyes to a completely new universe. His work is the best example of how art and research can join to create success. For me, THE decisive detail in his procedure for creating art – and every R & D department, including their management, could take a leaf from his book: Thomas Schönauer is deeply preoccupied with the very essence of matter, he feels his way into it, grants it the freedom to unfurl under his guidance, subordinates himself at the right moment to the process of creation, relinquishes control to allow what is new to break ground – is that, besides all his creative input, he is an entrepreneur willing to take risks, who works with all the factors familiar to us and connecting us. We can still learn plenty from Thomas Schönauer’s radicalism.

The lasting success of Aluminium Rheinfelden has provided us, a family of entrepreneurs, with the generous financial means to support Heaven’s Cross. To enable and to promote art in public space is in our view a vital contribution both to the enrichment of our society and to the success of socio-cultural encounters “beneath the open sky”. With these Heaven’s Crosses we wish to lend expression to our conviction and to our deep roots in the Western Christian culture. We bow to the achievements and immense courage of Martin Luther, whose enormous innovative power we are celebrating today, 500 years later, in such a great, peaceful and ecumenical way. Being part of the newly built park fills us with tremendous pride.

“May the Heaven’s Crosses in their reclined, floating beauty surging to the heavens open the eyes of many visitors to repeatedly see and reflect on the familiar over and again.”

Heaven’s Cross in the Luther Garden

On the site of the city’s ramparts near the Schlosskirche (All Saints’ Church), made famous as the place where Martin Luther nailed up his 95 Theses, the Luther Garden forms a verdant gate into Wittenberg’s Old Town. It was created to commemorate the revolutionary event that took place 500 years ago inside the city walls and which changed the world.

In spring 2014, when landscape architect Andreas Kipar presented his plans for the Wittenberg Luther Garden to the board of trustees of the “Lebendige Stadt” (Living City) Foundation, and requested our financial support for Heaven’s Cross, the anniversary of the Reformation was already looming large on the horizon. It did not take long for Andreas Kipar to captivate the trustees with his enthusiasm for the Luther Garden: a park planted with 500 trees from all over the world, whose paths were laid out in the shape of a Luther rose and led outwards from the Heaven’s Cross into the world – like the idea of the Reformation 500 years ago.

Designed by artist Thomas Schönauer, the monumental cross is made of polished steel and forms a pendant to the greenery of the surrounding garden, whose design is itself a work of art. Despite its size, the Heaven’s Cross has a lightness and reminds one a little of balancing wings. And it is precisely this balance that visitors experience in this inspiring place of nature and art, in the form of inner harmony and tranquillity. Walking towards the Heavenly Cross, we feel the cohesion of the many Christian world communities that have planted trees with plaques of origin on the left and right. The large number of trees illustrates this global fellowship. Beneath the Heaven’s Cross, our eyes turn heavenwards wholly of their own accord.

The Luther Garden is an inner-city green oasis that invites people to slow down, reflect and exchange ideas – preferably also in fellowship with others: cross-generational, gender-independent, intercultural and cross-denominational. That is what distinguishes the vibrancy, diversity and tolerance of a city. And that is also precisely what the Lebendige Stadt foundation is all about. The foundation has already supported the Essen Krupp Park designed by Andreas Kipar and the restoration of the Civic Gardens in Arnsberg. The Luther Garden in Wittenberg is thus a continuation of its commitment to the care and design of inner-city green spaces.

The artistically designed garden may not ring in a new era like Luther’s Theses, but it will most certainly have a lasting effect. With the Luther Garden, a piece of “living city” has been created that symbolises the importance of the Reformation in an outstanding way. The “Lebendige Stadt” Foundation is delighted to have been able to make a contribution to this.

“And it is precisely this balance that visitors experience in this inspiring place of nature and art, in the form of inner harmony and tranquillity.”

Heaven’s Cross and the Luther Garden: The urban planning, architectural and artistic relevance of the project. An example of a new school of thought on the sculptural design of urban and landscape spaces.

Wittenberg did not suffer extensive destruction during World War II. Following German reunification, developmental projects for urban renewal in the city had to take into account particular tensions between, on the one hand, historical and cultural achievements with a European dimension in the fields of art, religion and science; and on the other, the authentic phenomenon of an original European city in the Elbe landscape.

From the early 1990s on, gaining official recognition for the ramparts around Wittenberg’s historic old town had also been on the agenda. Between 2008 and 2016, the Luther Park and the Luther Garden were established here, and on 15 June 2016, the sculpture Heaven’s Cross was unveiled in the centre of the Luther Garden. Wittenberg had a new “gesamtkunstwerk” (total work of art).

Tasks and expectations

In early 2008, the city of Wittenberg and the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) began putting serious thought into how the 500th anniversary of the events of 1517 should be celebrated in 2017. In Wittenberg, professing Christians make up around 14 percent of the population, but the whole city was keen to host the celebrations. A lively discussion got underway. The idea that ultimately took hold was to combine the renewal of the ramparts, which had been declared a garden monument, with the erection of a modern “monument to the Reformation”. And this was to be installed very close to the central market square with the Luther monument.

It was a twofold task. The city’s politicians and administrative bodies wanted to have the area around the city ramparts officially designated a public park. As a new recreational site close to the city centre, the Luther Park would improve the quality of life far beyond 2017 and be used by the whole of Wittenberg. What was planned for the city’s big event would later prove its worth in everyday life. The LWF, a church community, regarded this park as the ideal site for a symbolic memorial with global appeal. It was not to be a conventional monument, which above all stimulates memory, and thus a retrospective view. Instead, building upon the historical force of ecumenism, it should look to the future. People from different Christian churches on all five continents should be able to meet there. The communal bond with the birthplace of the Reformation should be anchored in heads and hearts in such a way that it is also effective at a distance.

To sum up the situation: on the one hand, a city park was to be developed in Wittenberg; on the other, the development of Christian congregations as part of world history was to be marked by creating a visibly dominant, ecumenical monument in and with the park for the celebrations in 2017. This presented a particular challenge in terms of creative design, even without the need to define the conditions for the project’s realisation and deal with the uncertainties of its implementation. The developers in Wittenberg – the city authorities and the LWF – had set a task and outlined quality expectations that demanded more than technical or functional urban planning and architectural competence, from the overall concept through to the finer details. The result should be able to assert itself alongside the city’s other historical and cultural achievements. The decision-makers and the citizens of Wittenberg – the later beneficiaries of the new urban space – were thus also given a task: they had to support the project and its results. This meant establishing and shaping communication.

The Luther Garden – finished but not complete

Andreas Kipar cut the Gordian knot. With his ingenious idea, he fulfilled the wishes of both the city authorities and the Christian community. Kipar conceived a permanent site based on the idea of planting an apple tree – a confession of faith that is ascribed to the reformer Martin Luther and can be applied to all human times. This site was created with growing, living nature and incorporated creative motifs from garden art of the baroque and Renaissance periods. With this modern “architectural garden”, it is as if Andreas Kipar wanted to fulfil Marie Luise Gothein’s hope for her “History of Garden Art”, which was first published in German in 1913: “My wish is that they [the artists of today, D. M.] may find not so much a storehouse of the ideas of great masters of the past, as an abundant harvest for their own creations in the present day!” (Gothein 2014, foreword).

Andreas Kipar designed a very special city park, also with regard to the realisation process, as it was to be planted with the participation of different Christian communities from all over the world: the Luther Garden. The Luther rose on the ground with its embedded stone cross marks the central space. The symbolic and iconographically formed elliptical paths give structure to the park with its lightly modelled terrain. From the outset, the successive planting of young trees guaranteed an animated process of growing and becoming.

“A lively discussion got underway. The idea that ultimately took hold was to combine the renewal of the ramparts, which had been declared a garden monument, with the erection of a modern ‘monument to the Reformation’. And this was to be installed very close to the central market square with the Luther Monument.”

“The architectural/urban planning objective underlying this idea was that the garden should one day be a new, tangible landmark, along with Wittenberg’s two other symbolic Christian buildings that are visible from afar: the Schlosskirche (All Saints’ Church) and the Stadtkirche (St. Mary’s).”

The image of the garden inside and beyond the city walls is deeply rooted in our minds. The name “Luther Garden” already defined this area before a single tree had been planted. The optimistic and hopeful idea of the Luther Garden was spread and became firmly established through informal conversations as well as formal discussions accompanied by texts and pictures. Although there was some initial resistance against the idea of creating an “orchard” in the park around the city ramparts, with the possibility of a wasp plague at harvest time, the local politicians were convinced by and gave their backing to the dynamic design concept. The idea of erecting a monument in the form of an ecumenical Luther Garden “as a symbol of reconciliation and mutual understanding” was adopted and promoted not only by the LWF, but by Christians from all over the world. This garden idea was to be carried around the globe by planting a second “little tree in kindred spirit” in the home parish of a distant country. The Luther Garden is a work of garden art for our time.

The Luther Garden had to be large enough to plant a total of 500 trees. The “Luthergarten an der Andreasbreite”, located close to the market square and beyond the city moat, had space for 292 trees, 80 of which were to be fruit trees. The city’s concept for the park around the city wall aimed to create a tour of the old town. The consequences for the Luther Garden project were obvious: in addition to the area around the fortifications, two further areas were allocated to enable 500 trees to be planted by Christians from all over the world – the Luther Garden by the new Town Hall in the north, and the area by the Luther House in the east. The Luther Garden took on a whole new dimension: it was now present in the everyday life of the whole city. A Luther Garden triad in “Lutherstadt” Wittenberg.

The “Luthergarten an der Andreasbreite” is the central outdoor venue for Christian events in the city. Here, in the area around the Luther rose, the foundation stone for the new garden was laid on 20 September 2008. A number of events proved the suitability of the location. The Christian symbol on the ground transformed it into a place of devotion. The site was far from complete, however, as can be seen in photographs taken at the inauguration on 1 November 2009, when the first 25 trees were planted. Even later, when many fruit trees had already borne fruit, the central area marked by five symbolic lime trees looked like an empty space in the overall structure of the garden. This emptiness was also emphasised by the fact that all the paths led to the Luther rose. If you did not look down at the ground when you reached this spot, your (unconscious) expectations of this central location were not met. The dimension of volume was missing. The site did assume voluminous form and seem more complete, however, when people stood in a circle while a church service was being held. The landscape architect was not the only person who felt that the Luther Garden was not yet finished.

What was missing from the Luther Garden?

The architectural/urban planning objective underlying this idea was that the garden should one day be a new, tangible landmark, along with Wittenberg’s two other symbolic Christian buildings that are visible from afar: the Schlosskirche (All Saints’ Church) and the Stadtkirche (St. Mary’s). Towering above the historical cosmos behind the city wall and ramparts, these symbolic cornerstones of the Reformation still provide orientation within the city. Not only intellectually, but also visibly and spontaneously perceptible, the Luther Garden was intended to be experienced as part of the Christian-influenced symbolic trinity. Non-Christians and atheists, however, may perceive it differently – perhaps only as part of a triad of dominant urban landmarks.

Invisible elements also had to be incorporated into the design. Questions arose. What volume could fill this space around the Luther rose without “occupying” it? What should this “something” be which – rationally understood and emotionally experienced – embodies the overall ecumenical idea without questioning the Luther Garden’s function as a secular element of Wittenberg’s new public park? Don’t the adjoining spaces on every side of the Luther Garden and its new paths demand even greater and lasting presence in what is supposed to be its centre?

To the east of the garden is the popular and much used playground “Spielpark am Lutherpark Andreasbreite”; redesigned with sculptural wooden elements under the heading “Microcosm” and subsidised by the LWF, it reopened on 23 July 2014 and seems like a natural part of the Luther Garden. To the west is the adjoining meadow whose expanse makes the approach to the Luther Garden such a unique experience. To the south is the viewing and walking axis that leads from the railway stop “Wittenberg-Altstadt” on the Old Town through the middle of the Luther Garden to the city centre. And to the north is the entrance flanked by two magnificent old trees, a dam in the city moat that leads directly to the Luther rose laid out on the ground, along with the “Wallgarten” (rampart garden) circular path that passes by here.

Last but not least was the question: how can the designation “The Luther Garden – a living monument of the Reformation”, which was already being used for city marketing purposes, be made more visible, more memorable and thus perhaps more comprehensible for the naive eye, in accordance with its international significance?

The Luther Garden, especially its centre, was however not intended to be a “sacred grove” or a “place of God”. It was to be a place of encounter, but a special kind of encounter. Devout visitors from all over the world and Christians from Wittenberg should be able to sense why they are gathering under the treetops of the Luther Garden, rather than on the city’s market square, just 400 metres away, where the Luther Monument stands that was created in 1821 by the artist Johann Gottfried Schadow and the architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Even if they don’t know it, walkers in the park should sense that they are approaching a place of special importance.

Such a task cannot be achieved solely with technical, functional and constructive thinking and action. It also requires artistic creation. The architect Bruno Taut summarised the effects of different forms of artistic creation in his “Lectures on Architecture”, which were written in 1936/37 while he was in exile in Istanbul, but were not published in German until 1977 and are far too rarely studied. At the end of the last chapter, “Relations to society and to the other arts”, he writes: “The forms of art provide support for emotion, those of architecture support a sense of proportion, i.e. a sense that something is well ordered, divided and structured” (Taut 1977, p. 192). It is an appeal for collaboration.

Questions regarding the completion of the so carefully developed Luther Garden, which became increasingly visible with new tree plantings and thus easier to assess within its surroundings, increased and became more concrete. Did the Luther Garden lack “the forms of art”? Many discussions with the clients yielded ideas for the space around the Luther rose. For example, that of building a stone cross on which people could sit. All of these ideas were dismissed, however, and the decision was made to ask artists to become involved. It was and still is quite common to find a solution by holding an (international) art competition, but this plan had to be abandoned due to cost and time restrictions.

The idea: “Heaven’s Cross”

It is, and always has been, possible to find a way when people come together “who speak the same language” and are above all committed to finding the best – the most ideal – solution to a problem. The discussion between the landscape architect Andreas Kipar and the artist Thomas Schönauer, which also deepened in the Wittenberg project, ended with the architect’s request: “Go and have a look at this in situ.” Thomas Schönauer did precisely that. After three days, it is said, he presented his ingenious idea and named what could perfectly complete the Luther Garden: “Heaven’s Cross”. He described the idea as follows: “Based on the idea of the Holy Trinity and, in formal terms, the skyward growth of the trees, two additional, diverging cross structures hover above the cross construction that is set into the ground.”

This basic idea, which Thomas Schönauer presented with the aid of a small model, was already contained like an invisible seed within Andreas Kipar’s concept for the Luther Garden. It was as if it had needed time to grow, and above all the help of his artist friend Thomas Schönauer, to bring it to life and give it a name.

Not only the architect, but all decision makers in the LWF and the city’s various political factions quickly agreed that the “Heaven’s Cross” idea provided the perfect solution. Such unanimous agreement was surprising. Pastor Hans W. Kasch, who is in charge of organisation in the LWF’s Wittenberg branch, believes that people were prepared to accept the “forms of art”, as the previous process of planning the Luther Garden had promoted understanding and changed perceptions. Which definitely sounds plausible.

The majority of those involved may not have perceived one fundamental quality of the “artistic architectural installation”, but they probably sensed it. Even just the model of “Heaven’s Cross” unconsciously signalled a psychologically justifiable change of behaviour towards the cross embedded in the ground inside the Luther rose. Devout Christians may have perceived it as a message. The head and gaze look down upon the cross on the ground – a symbol of faith – like a gravestone. This posture corresponds to and signals grief or aversion – a turning away. Thoughts are directed into the past. But now the cross was suspended in the sky. The cross in the earth had not been replaced. It was raised up as the phenomenon of a double cross. Whether viewers are standing or sitting on this spot, their gaze can soar upwards, past the gleaming, suspended crosses and into the clouds. This signals a turn towards the world – a future. It can also mean hope. Christians might think of the joyful Easter message of the resurrection when they see the crosses. Spreading hope was a central theme of the Luther Year 2017.

“Even if they don’t know it, walkers in the park should sense that they are approaching a place of special importance.”

The implementation of the idea

The will to implement the idea was as strong as the financial situation was weak. Many people helped to make it happen. The project title in the funding application submitted jointly to the Hamburg foundation “Lebendige Stadt” at the beginning of 2014 by the LWF, Oberkirchenrat Norbert Denecke, and the Lord Mayor of the City of Wittenberg, Eckhard Naumann, was: “Luthergarten 2017. Central venue with art installation in the Luther rose”. The aim for the “art installation” was outlined as follows: “For the festivities in 2016 and 2017, the heart of the Luther Garden in Wittenberg is to be accorded special significance.” Andreas Kipar presented the overall concept. The idea of Heaven’s Cross and the commitment of the various protagonists were convincing. Nevertheless, there were some sceptical questions with regard to as yet unsolved technical or functional issues (materials, rain drainage, wind loads, soiling and vandalism). Even a “Heaven’s Cross” needed time to grow.

As with any building, in addition to the main problem of financing, there were more things to consider and clarify than initially expected. Facing these challenges required more than just the artist’s own work in his Düsseldorf studio. Teamwork was called for. The responsible authorities and individuals in Wittenberg, along with the sponsors and the artists, convened in a new project group called “Artistic Design of the Luther rose in the Luther Garden in Wittenberg”. When this group first came together on 23 July 2014, the day of the reopening of the playground “Spielplatz am Lutherpark Andreasbreite”, one of their first tasks was to come up with an “official designation” for the process that was getting underway. What is the essence of Heaven’s Cross? The members of the project group calmly and confidently agreed upon “The artistic architectural installation: Heaven’s Cross in the Luther Garden”.